|

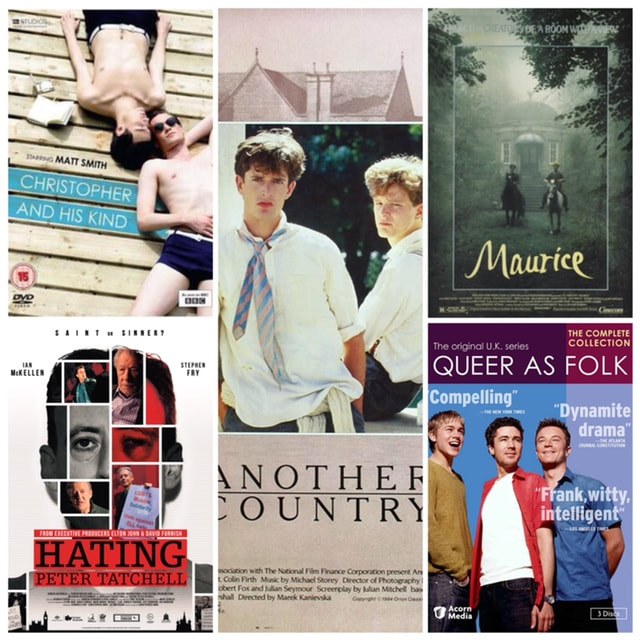

We're halfway through Pride Month and as it is 50 years since the first UK pride, I got to thinking about some of my favourite British LGBTQ+ films/ programmes. This is by all means not a definitive list and I am sure I could name more but in the interest of starting a conversation, here are 10 of my favourites in no particular order of preference.

1. Heartstopper: This current Netflix series is centred on Charlie, a recently outed teen and his growing relationship with Nick, a bisexual boy in his school. Set at an all boys school, the show deals with their respective group of friends and the drama that ensues when their relationship becomes known. Coming out is the overall theme in the series and as it has been renewed for another two seasons; I'm looking forward to seeing how the characters and storylines develop from there because as we know, coming out is only the beginning. 2. Beautiful Thing: This film adapted from Jonathan Harvey's 1993 play stole our hearts in 1996. Set on the Thamesmead Estate in SE London, it follows Jamie & Ste who's growing awareness and blossoming love is chronicled during one of London's hottest summers. It is one of the first major LGBTQ+ films of the 90's that did not have an underlying storyline that involved HIV/ AIDS or death. Doesn't seem like much but ground breaking in itself. 3. Get Real: Another play adapted into a film, which sadly did not receive the same accolades that Beautiful Thing did. Both films dealt with teenage sexual awakening but were two different types of story and had they been treated as such, perhaps it would have been better received. In this film, Steven is aware of his sexuality but not out. He spends his school days lusting over John, the popular kid at school and star athlete. After school he looks for hook ups to satisfy his awakening sexual appetite. When the two run into one another outside of school, it sets off a chain of events that will change both of their lives. 4. The Naked Civil Servant: Adapted from the memoirs of Quentin Crisp, and starring John Hurt, this film takes us through the early days of Quentin's life in London and filled with the witticisms and observations that would come to define his work. 5. Victim: This 1961 film was the first English language film to use the word "homosexual." Dirk Bogarde stars as a respected lawyer who falls prey to a blackmailer because of his affair with a young builder; as well as the fallout from it. It was ground breaking at the time and began a conversation about the crimes that were created as a result of homosexuality being illegal, particularly blackmail. I recently shared a piece I had written about this film which can be read here. 6. Hating Peter Tatchell: This documentary is a must see for any LGBTQ+ worldwide but in particular those of us here in the UK. Peter has devoted his life and sacrificed his own health and safety for the cause of LGBTQ+ equality and human rights around the world. Aptly titled, he remains a controversial figure but like activists' such as Larry Kramer, we must acknowledge that it is their tenacity and fierce approach that has been needed to press the accelerator on LGBTQ+ equality. You don't have to like him, but you need to respect him. 7. Christopher and His Kind: This BBC production stars Matt Smith as Christopher Isherwood and is based on the book of the same name. In this adaptation, we follow Christopher to Berlin in the last days of the Weimar Republic, his relationship with a young German whom he tries to help escape Germany and their reunification after the war in a divided Berlin. Isherwood's few years in Berlin would inspire the musical Cabaret and although he would spend the rest of his life in California, his Berlin years would come to define his literary work. 8. Maurice: Starring James Wilby as the title figure and Hugh Grant as his love interest. What makes Maurice such an important work is that E.M. Forester wrote the original novel in 1913-14 and later revised it with explicit instructions that it be not published until after his death. It chronicles the life of Maurice Hall and his homosexuality as reflected in early 20th Century England. Forester wanted the book to have a happy ending and wrote it as such. This put him at odds with the law but nevertheless he gave Maurice, the ending in which two men could be happy together. That love could exist between two men even when the odds were against them. 9. Another Country: Based on the life of Guy Burgess, one of the Cambridge Five, it stars Rupert Everett & Cary Ewes as well as Colin Firth. Told in reverse from Guy's exile in Moscow after being outed as a Russian spy, it exposes the cruelty, coldness and hypocrisy of the British public school system. It was also the first ever LGBTQ+ film I ever watched, one late night on PBS. I had never seen two men embrace in a film until then and it stuck with me. 10. Queer As Folk: This series is now on its second reincarnation in the form of another US adaptation but in this moment, I am referring to the original. I don't think there is a single person who can't remember the premiere episode that follows a group of friends in Manchester who are living, loving and fucking their nights away. I wrote a piece last year about it for Gay Life Manchester which you can read here. I wrote a piece last year for Gay Life Manchester Magazine on this show’s enduring popularity which can be read here. So not a definitive list but a start, what are your favourite UK LGBTQ+ films and programmes? Share them in the comments, on social media or feel free to message with them. Happy Pride Everyone!

0 Comments

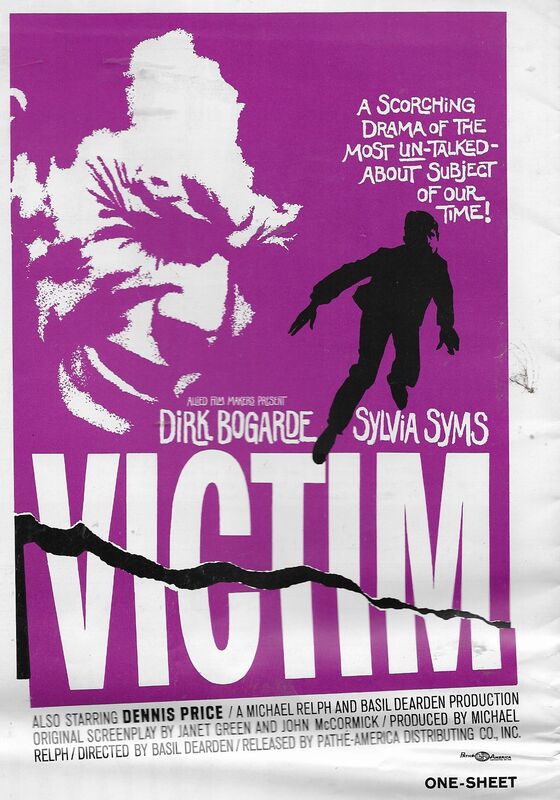

60 years ago this August the film Victim starring Dirk Bogarde premiered. It was the first English language film to use the term “homosexual.” The film centres around the blackmail and subsequent suicide of Jack “Boy” Barrett who was protecting his friendship with married solicitor Melville Farr (Bogarde) just as he is about to be named Queen’s Counsel. The film uses friendship/ relationship interchangeably because the relationship between Jack and Melville is never consummated but is intimate enough to arouse suspicion and make them the target of blackmail. Victim is not often thought about these days because of how far LGBTQ+ rights have progressed since 1961. It is though one of the most important films for British LGBTQ+ History and one that is still relevant today. Homosexuality is no longer illegal but blackmail of LGBTQ+ individuals is still a reality.

Janet Green and her husband John McCormick wrote the screenplay for Victim after reading The Wolfenden Report which was commissioned in 1957. The Report recommended that homosexual acts between consenting adults be made legal, thus replacing the existing Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 which made all homosexual acts between men illegal. It also recommended the age of consent be 21. The recommendations were not put into law until the passage of the Sexual Offences Act 1967 which then legalised homosexual acts between men as long as they were consensual, in private and both men were 21 or over. The husband and wife team were no strangers to tackling social issues having previously written the screenplay for Sapphire; detailing the rising racial tensions with the arrival of Afro-Caribbean immigrants in the 1950’s, known today as the “Windrush” Generation. Victim begins with the police coming to arrest Jack “Boy” Barrett at the building site where he works. Jack escapes and we learn that he is being investigated for the theft of £2300, which the Police suspect has been used to pay off a blackmailer. Jack seeks help from his friend Eddie to remove some incriminating evidence from his lodgings including a scrapbook he had made of Melville Farr’s career. He tries to contact Melville to warn him but is rejected when Melville for help, including former lover and bookseller Harold Doe. Jack is caught on the run and arrested as he is trying to destroy the scrapbook. He refuses to give up any names and hangs himself in the detention cell. By this time, the police have pieced enough of the book to know Melville Farr is somehow tied to the case but unsure how. Eddie visits Melville and shows him the photo that Jack was protecting; it was of he and Melville sat together in a car. In the photo, Jack is crying. The perceived intimacy in the photo was enough to imply a relationship although later on even Melville concludes that a good solicitor could have argued that out of a court. So why does he embark on a mission to expose the blackmailers and risk his entire marriage, reputation and career? As the story unfolds, we learn that Melville had a relationship at Cambridge with another man who committed suicide because Melville was frightened of his own sexuality. His wife was fully aware of this and he swore that he would never act on his impulses again. He keeps his promise and although he strikes a friendship with Jack, it isn’t until he can’t control his emotions that he ends it, which is the catalyst for the film’s events. It is perhaps the guilt of both deaths that makes Melville realise that enough is enough. Although he starts out as a lone avenger, once he realises the scale of blackmail and the layers to it, he decides to enlist the police and out himself in open court rather than let the blackmailers. It is worth noting that we never see the court case itself most likely because the law itself still made homosexuals criminals as much as the blackmailers, if not more so? In terms of representation by our standards now, the film is problematic. The main character is not a practising homosexual. This could be that the portrayal of such an act would have not been allowed by law or the censors, who had already taken issue with the film prior to its premiere at The Odeon in Leicester Square. The other homosexual characters are portrayed as weak. They live in fear or are pushed to commit crimes to pay for their “crime of existing.” The “accepting” heterosexual characters are still homophobic in their assessments of their friends. They tolerate them as best as they can because of their humour as we see in the case of Madge, a model who frequents The Salisbury, a notorious gay pub since the days of Oscar Wilde. They pity homosexuals as much as they are disgusted by the acts they commit. There is also paranoia that homosexual predators are everywhere. There is a belief that society is too permissive and descending into a “degenerate” state. When the blackmailers are revealed, they show no remorse as well as an absolute disgust for homosexuals. They even go as far as to say they are doing the work that the police refuse to do and punishing homosexuals as they should be. Language-wise, I don’t think there is anything said that most of us haven’t heard by now but in 1961, it certainly wasn’t said in cinema until Victim premiered. That said, the film holds a mirror up to the hypocritical nature of 1960’s British society. The Police Captain refers to the law that punishes homosexuality as “The Blackmailer’s Charter.” The law itself created a rise in blackmail. Victims of blackmail were often forced to commit other crimes because effectively they were born criminals. They couldn’t got to the police to report blackmailing without fear of being arrested themselves. As in espionage, secrets are a valuable currency and the cost to many homosexuals being outed at that time was a price too high to pay. You would lose all social standing, income, family and friends. If sentenced to prison, homosexuals were often the lowest class of prisoner and subjected to horrendous abuse by both prisoners and staff. The fear alone kept these victims from coming forward. As Calloway, a blackmailed character in the film says, “Why should I be forced to live outside the law because I find love in the only way I can?” Today we are free to love and marry by law. We cannot be discriminated against in housing or employment by law. Yet, blackmail is still on the rise. The law can be argued doesn’t always work in our favour and this too can fuel blackmail. The National Office of Statistics reported a total of 46,429 blackmail offences in England Wales in the last 5 years with nearly 11,000 in the last year alone. It is worth noting that figure isn’t entirely LGBTQ+ related. Galop (the UK’s LGBT+Anti- Abuse charity) surveyed over 700 LGBT+ people and found that in the last five years, 14% had experienced blackmail. Outing and Doxing (releasing personal information with malicious intent) were experienced by 34% and 21% of respondents respectively. In the first half of 2020, there were three high profile cases in the UK in which defendants were charged for blackmail, including a teenager who lured men on Grindr and then threatened to expose them. Although the law is on our side, the fear and shame keep many vulnerable older men in particular from seeking justice. Blackmail though is not just the concern of older men, only recently Colton Underwood, The Bachelor contestant was blackmailed with photos of him leaving a gay sauna prior to coming out publicly. “Fear is the oxygen of blackmail” says Melville Farr in the film and ultimately what Victim sheds a light on, is how a culture of fear furthered a criminal enterprise. Fear that society would collapse into a degenerate state kept anti-homosexual laws in place. Fear that others would think homosexuality was okay kept homosexuals from living open and healthy lives. Fear of being outed kept many homosexuals paying the high price of what Harold Doe in the film says, “nature’s dirty trick.” The fact that blackmail is reported and cases are prosecuted is a massive step forward from 1961. That said, without eliminating the fear, shame and stigma of homosexuality that fuels this crime, LGBTQ+ People remain susceptible to victimisation. |

AuthorJohn Lugo-Trebble considers this more of a space to engage personal reflections and memories with connections to music and film. Archives

November 2023

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed